“Nothing resembles a dream more than a ballet, and it is this which explains the singular pleasure that one receives from these apparently frivolous representations. One enjoys, while awake, the phenomenon that nocturnal fantasy traces on the canvas of sleep; an entire world of chimeras moves before you.”

-Theophile Gautier, French poet

Ballet is the epitome of classical dance in Western cultures. Classical dance forms are structured, and stylized techniques developed and evolved throughout centuries requiring rigorous formal training. Ballet originated with the nobility in the Renaissance courts of Europe. The dance form was closely associated with appropriate behavior and etiquette. Eventually, ballet became a professional vocation as it became a popular form of entertainment for the new middle-class to enjoy. Ballet spread throughout the world as dance masters refined their craft and handed their methods down from generation to generation. Over 500 years, it has developed and changed. Dancers and choreographers worldwide have contributed new vocabulary and styles, yet ballet’s essence remains the same.

Ballet is a codified dance form ordered systematically and has set movements associated with specific terminology. Ballet is a rigorous art and requires extensive training to perform the technique correctly. The first ballet creators’ principles have survived intact, but different regional and artistic styles have emerged over the centuries. Ballet classes follow a standard structure for progression and are comprised of two sections:

The first part of ballet class typically begins with a warm-up at the barre. The barre is a stationary handrail that dancers hold while working on balance, allowing them to focus on placement, alignment, and coordination. The second half of the ballet class is performed in the center without a barre. Dancers use the entire room to increase their spatial awareness and perform elevated and dynamic movements.

Ballet emphasizes the lengthening of the spine and the use of turnout, an outward rotation of the legs in the hip socket. This serves both to create an aesthetically pleasing line and increase mobility.

Ballet demands a strong articulated foot to perform demanding movements and create an elongated line.

Pointe shoes, a ballet staple, add to the illusion of weightlessness and flight. They are constructed with a hard, flat box to enable dance on the tips of the toes; it is a technique called en pointe that requires years of training and dedication to develop the needed strength in the feet, ankles, calves and legs.

Traditionally, ballet favors a light quality, called ballon, with elevated movements. Dancers seem to overcome gravity effortlessly and achieve great height in their leaps and jumps.

Ballet can tell a story without words through a language of gestures called pantomime. Some movements are easily understood or have simple body language, but more abstract concepts are given specific gestures of their own to convey meaning. The facial expressions, the musical phrasing, and dynamics all play a role in communicating the story. Pantomime developed in ballet’s Romantic period and was further incorporated during the Classical era.

Watch This

The Royal Ballet dancers demonstrate and decode ballet pantomime for Swan Lake. David Pickering addresses the audience in the basics of pantomime, and audience members mimic the movement. In the second part of the clip, principal dancers Marianele Nunez and Thiago Soares reenact Act 2 as David Pickering narrates the pantomime.

In medieval Italy, an early pantomime version featured a single performer portraying all the story characters through gestures and dance. A narrator previewed the story to come, and musicians accompanied the pantomime. Pantomimes were quite popular, but they were sometimes over-the-top in their efforts to be comedic, often resulting in lewd and graphic reenactments. Dance was a part of everyday life. Peasants danced at street fairs, and guild members danced at festivals, but it was in the royal courts that ballet had its genesis.

Catherine de’ Medici, a wealthy noblewoman of Florence, Italy, married the heir to the French throne, King Henri II. In 1581, she went to Paris for a royal wedding accompanied by Balthazar de Beaujoyeulx, a dance teacher and choreographer. Catherine de’ Medici commissioned Beaujoyeulx to create Ballet Comique de la Reine in celebration of the wedding, and it became widely recognized as the first court ballet. The ballet de cour featured independent acts of dancing, music, and poetry unified by overarching themes from Greco-Roman mythology. The ballet included references to court characters and intrigues. After the Ballet Comique de la Reine production, a booklet was published with libretto telling the ballet story. It became the model for ballets produced in other European courts, making France the recognized leader in ballet.

During King Louis XIV’s reign, France was a mighty nation. King Louis XIV kept nobility close at hand by moving his court and government to the Palace of Versailles, where he could maintain his power. At court, it was necessary to excel in fencing, dance, and etiquette. Nobility vied for an elevated position in court as one’s abilities in the finer arts reflected success in politics.

King Louis XIV was a great patron of the arts and vigorously trained in ballet. He performed in several ballet productions. His most memorable role was Apollo, gaining the title the “Sun King” from “Le Ballet de la Nuit,” translated to “The Ballet of the Night.”

Louis XIV’s love of dance inspired him to charter the Académie Royal de Musique et Danse, headed by his old dance teacher Pierre Beauchamps and thirteen of the finest dance masters from his court. In this way, the king assured that “la danse classique,” that is to say, “ballet,” would survive and develop. The danse d’ecole provided rigorous training to transition from amateur performance to seasoned professionals. This also opened the door for non-nobility to pursue ballet professionally. For the first time, women were also allowed to train in ballet. Women were only allowed to participate in court social dances until this point. Men performers took on all the roles in court ballets, wearing masks to dance the roles of women.

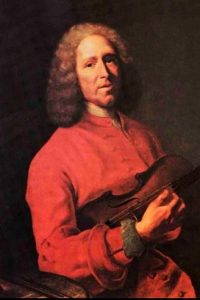

Transitioning from the ballet de cour, dances of the Renaissance ballroom grew into the ballet a entrée, a series of independent episodes linked by a common theme. Early productions of the academy featured the opera-ballet, a hybrid art form of music and dance. Jean-Philippe Rameau served as both composer and choreographer for many early opera-ballets.

At this time, there was a differentiation of characters that dancers assumed. These roles were generally categorized as:

Some significant developments aided in the progression of ballet as an art form at the Académie Royale de Musique et Danse. Pierre Beauchamps significantly contributed to ballet by developing the five basic positions of the feet used in ballet technique. He also laid the foundation for a notation system to record dances. Raoul Auger Feuillet refined the notation and published it in 1700; then, in 1706, John Weaver translated it into English, making it globally accessible.

Watch This

In this split-screen, Feuillet’s dance notation is shown on the left side while dancers perform the Baroque dances on the right side.

The Académie Royale de Musique et Danse was the place to train classical dancers. Dancers and dance masters alike traveled to the great centers of Europe, bringing French ballet to the continent. Today’s Paris Opera Ballet is the direct descendant of the Académie Royal de Musique et Danse.

Watch This

The TED-Ed animated video clip summarizing the origins of ballet.

The Age of Enlightenment was a philosophical movement that emphasized freedom of expression and the eradication of religious authority. These ideas caused criticism among philosophers who believed art forms should speak to meaningful human expression rather than ornamental art forms.

Ballet master and choreographer Jean-Georges Noverre challenged ballet traditions and made ballets more expressive. In his famous writings, Letters on Dancing and Ballet, Noverre rejected dance traditions at the Paris Opera Ballet and helped transform ballet into a medium for story-telling. The masks that dancers traditionally wore were stripped away to show dramatic facial expressions and convey meaning within ballets. Pantomime helped tell the story of the ballet. In addition, plots became logically developed with unifying themes, integrating theatrical elements. From Noverre’s concepts, ballet d’action emerged.

Carlo Blasis was particularly influential in shaping the vocabulary and structure of ballet techniques. He invented the “attitude” position commonly used in ballet from the inspiration of Giambologna’s sculpture of Mercury. He published two major treatises on the execution of ballet, the most notable, “An Elementary Treatise Upon the Theory and Practice of the Art of Dancing.” Blasis taught primarily at LaScala in Milan, where he was responsible for educating many Romantic era teachers and dancers.

During the Renaissance, men and women wore elaborate clothing. Women wore laced-up corsets around the torso and panniers (a series of side hoops) fastened around the waist to extend the width of the skirts. Men wore breeches and heeled shoes. The upper body was bound by bulky clothing and primarily emphasized footwork. By the 18th century, there were changes in costuming. Two dancers helped revolutionize costumes.

Marie Sallé was a famous dancer at the Paris Opera, celebrated for her dramatic expression. Her natural approach to pantomime storytelling influenced Noverre. She traded the elaborate clothing that was fashionable at the time to match the subject of the choreography. In her self-choreographed ballet “Pygmalion,” she wore a less restrictive costume, wearing a simple draped Grecian-style dress and soft slippers. This allowed for less restricted movement and expression.

Marie Camargo, a contemporary of Sallé, exemplified virtuosity and flamboyance in her dancing. She shortened her skirt to just above the ankles to make her impressive fancy footwork visible. She also removed the heels from her shoes, creating flat-soled slippers. This allowed her to execute jumps and leaps that were previously considered male steps.